Mexican migrant workers harvest parsley on a farm in Wellington, Colo. – John Moore/Getty Images

Kathleen Sexsmith, Penn State; Francisco Alfredo Reyes, Penn State, and Megan A. M. Griffin, Connecticut College

Television crime shows often are set in cities, but in its third season, ABC’s “American Crime” took a different tack. It opened on a tomato farm in North Carolina, where it showed a young woman being brutally raped in a field by her supervisor.

“People die all the time on that farm. Nobody cares. Women get raped, regular,” another character tells a police interrogator.

The show’s writers did their research. Studies show that 80% of Mexican and Mexican American women farmworkers in the U.S. have experienced some form of sexual harassment at work. Rape is common enough for some to nickname their workplace the “fields of panties.” For comparison, about 38% of women in the U.S. report experiencing some kind of workplace sexual harassment.

In a recent report, the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization called for transformative changes to the formal and informal social systems that disempower women who work on farms and in the food sector around the world. While violence against women in agriculture may seem like an issue mainly experienced in developing countries, the truth is that it also happens all too often to women and girls on farms in the U.S.

As we see it, sexual exploitation perpetrated by men in positions of power instills fear that keeps farm laborers obedient, despite precarious working conditions – and keeps fruits and vegetables cheap.

Vulnerable workers

In our research on rural development, agriculture and rural gender inequality, we have found that gender-based violence against female workers is frighteningly common on U.S. farms.

According to the U.N., violence against women and girls includes “any gender-based act that creates sexual, psychological, or physical harm or suffering.” Men and boys can, of course, experience gender-based violence on U.S. farms, but to our knowledge no corroborating research exists.

Most often, sexual violence against women is committed by men in positions of power, such as foremen, farm labor contractors, farm owners and co-workers. Unfortunately, farm workers often buy into the myth that women bring sexual harassment on themselves. This belief makes it difficult for victims to get support.

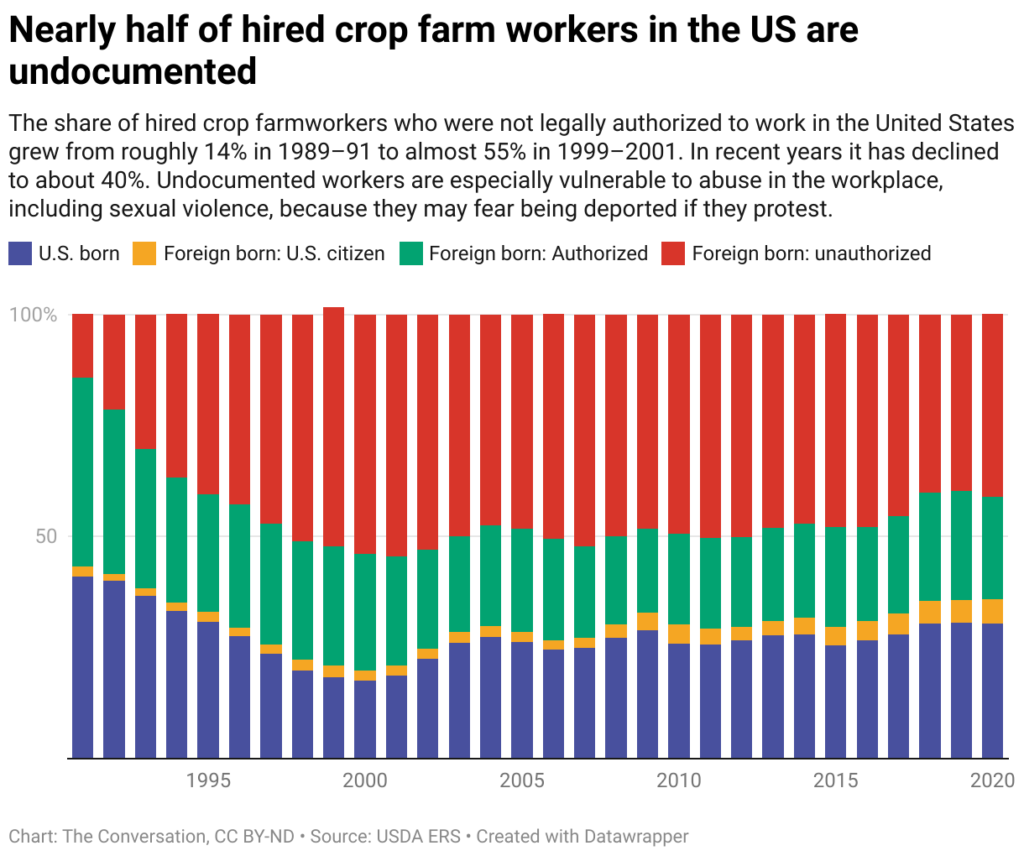

Immigrant women farm workers are vulnerable because of power imbalances in their male-dominated workplaces. Women represent 28% of the nation’s farm workers, making them a minority on many farms. Most are immigrants from Latin America, and many are undocumented.

Female farm workers also face a gender wage gap of about 6%, partly because of parenting responsibilities that limit the number of hours they can work. Researchers have documented how men in positions of power take advantage of this vulnerability by offering hours and job perks in exchange for sexual favors and threatening to fire women if they refuse.

Female farm workers also face a gender wage gap of about 6%, partly because of parenting responsibilities that limit the number of hours they can work. Researchers have documented how men in positions of power take advantage of this vulnerability by offering hours and job perks in exchange for sexual favors and threatening to fire women if they refuse.

The role of child labor

Girls under the age of 18 are particularly vulnerable to sexual harassment and abuse on farms. While much-needed reporting has generated a public outcry against arduous work conditions for migrant child laborers, migrant children have worked in agriculture in the U.S. for decades – legally.

Agriculture holds a special status under federal labor laws, which permit farm owners to hire children as young as 12. Facing low wages and high poverty rates, farm worker families often rely on income from children’s work.

Experts say young girls may be especially vulnerable to sexual harassment and violence on farms because they are less likely to recognize and report abuse. Currently, children as young as 12 can be hired on farms without a cap on the number of hours they work, as long as they don’t miss school.

Democrats in Congress have repeatedly introduced versions of the Children’s Act for Responsible Employment and Farm Safety (CARE) Act since 2005. The bill would help address the vulnerability of young girls in farm work by aligning the legal farm working age with other industries.

U.S. labor law allows children as young as 12 to work in agriculture, putting young girls at risk of sexual violence.

Are guest worker visas the answer?

Since one major driver of the threat of violence against female farm workers is the fact that many of them are undocumented, could expanding the national H-2A agricultural guest worker visa program be a solution?

The H-2A program has exploded in popularity among farmers as a way to address agricultural labor shortages. The number of U.S. farm jobs certified for H-2A workers increased from 48,000 in 2005 to 371,000 in 2022 as farmers pressed Congress to allow more foreign nationals into the U.S. to fill temporary agricultural jobs.

This program, at least in theory, addresses several of the structural vulnerabilities of female farm workers. A visa confers a legal right to enter the country, alleviating the severe risk of sexual assault during clandestine border crossings. Legal status should also eliminate fear of deportation, which would bolster women’s courage to speak up against sexual violence in the workplace.

But the key word here is “should.”

Concerningly, migrant labor advocates have charged that the H-2A program promotes “systemic sex-based discrimination in hiring.” Only 3.3% of H-2A guest workers admitted in 2021 were women, a level that reflects historical trends. Some foreign advertisements for H-2A workers explicitly state that recruiters are looking for capable male workers.

When female farm workers are few in number, they have less collective capacity to protest or report sexually abusive conditions. Moreover, one 2020 report on labor conditions among H-2A workers found that 12% of participants – including women and men – had experienced sexual harassment. The authors believed this figure represented a gross undercount.

Guest worker visa programs can actually make workers more likely to tolerate abusive situations, because the workers’ legal status in the U.S. by definition is tied to their employment. Guest workers are often particularly fearful of employer retaliation if they complain about sexual abuse. In our view, guest worker visa programs institutionalize workers’ uncertain position instead of solving it.

A path forward

We agree with the U.N. that sweeping change is needed to empower women, raise farm productivity and promote human rights in the global food system. As U.S. lawmakers craft the next farm bill, they could do enormous good for women around the world by setting an example in American fields and farms.

As a first step, we believe lawmakers should pass the CARE Act, which would raise the legal working age on farms to 14, reducing the number of young girls who are vulnerable to abuse.

Second, legalizing the nation’s approximately 283,000 unauthorized farm workers would make those workers less vulnerable to sexual abuse by expanding employment opportunities outside of the agricultural sector.

Third, in our view, efforts to legalize farm workers – most recently through the Farm Workforce Modernization Act – should strengthen labor law enforcement and provide well-funded channels for reporting abuses and changing jobs when abuse occurs.

Bills proposing a pathway to legalization for agricultural workers have focused on providing enough labor for farm employers. For example, some proposals would expand the H-2A program and require workers already in the U.S. to continue working in agriculture for a number of years to receive a green card.

But without steps to improve labor protection systems, such changes could make workers even more vulnerable to sexual and other labor abuses, and have the counterproductive result of making them more likely to want to leave agriculture as soon as they can.

Kathleen Sexsmith, Assistant Professor of Rural Sociology, Penn State; Francisco Alfredo Reyes, Ph.D. Candidate in Rural Sociology & International Agriculture and Development, Penn State, and Megan A. M. Griffin, Student Community Engagement Specialist, Connecticut College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()